Disruption has come for the aerospace supply chain

Blog

Anyone who found themselves rationing or hoarding toilet paper when the Covid-19 pandemic kicked off in 2020 has the words “supply chain disruption” etched permanently into their brain. At the same time, anyone who is back to tossing TP around with reckless abandon knows that most supply chain disturbances are temporary.

This post is about a different, permanent form of disruption that has come for the aerospace industry’s supply chain. Buckle up as we connect a few dots that lead to the undeniable realization that the entire aerospace supply chain is about to be totally remade.

Origin story: Cold War

One can’t understand where the aerospace industry is going without understanding where it came from. The modern aerospace supply chain – with “primes” at the top, followed by OEMs, system integrators, component manufacturers, and suppliers – was forged on the anvil of the Cold War.

After World War II, nations jockeyed for position in the global power hierarchy, leading to a technological arms race between the U.S. and Russia. With the power of atomic weapons demonstrated with devastating force in Hiroshima, it became clear that the specter of nuclear warfare was a powerful lever in global politics. Both the U.S. and Russia saw spaceflight demonstrations as paramount in establishing credibility in ballistic rocket capabilities. Winning the Space race became a matter of national security, especially after the reverberations of “Sputnik shock” from the U.S.S.R.’s first-ever successful space satellite launch in 1957.

Fueled by a visionary goal to reach the moon first, and the national security imperative of discouraging utter global thermonuclear annihilation, the U.S. mobilized a once-in-a-generation innovation apparatus to build the Apollo program. Of course, Apollo 11’s historic lunar landing wasn’t the only mission impacted by this unprecedented push for innovation. This effort created the modern aerospace supply chain, with implications on not only NASA’s space programs, but also defense aerospace programs funded by the Department of Defense and commercial aviation programs that made behemoths out of Airbus and Boeing.

A season of incrementalism

Any student of history knows that trends are cyclical. Fatigue and complacency almost always follow victory, and urgency returns only when a new timely threat or opportunity arises.

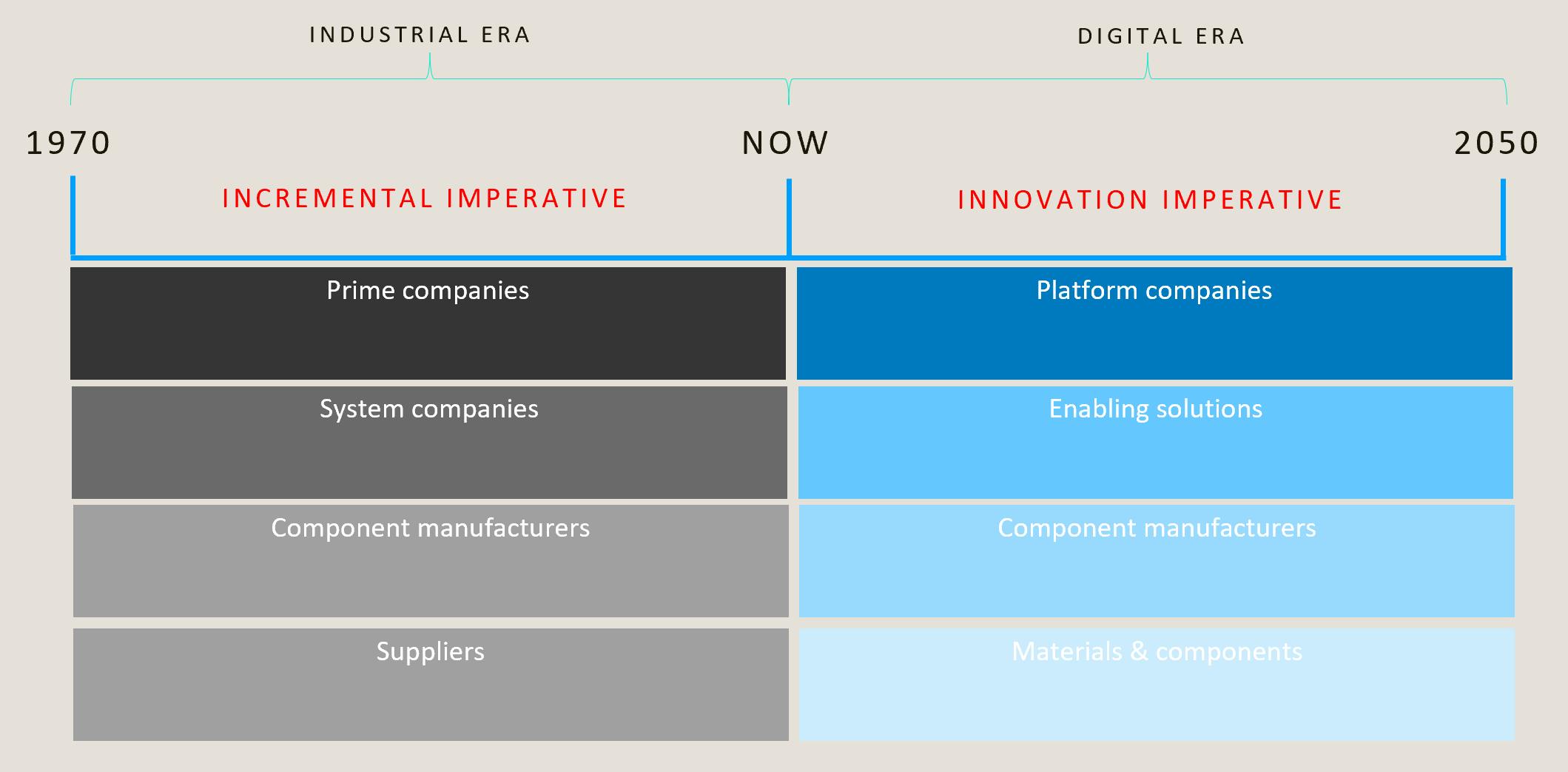

The urgency that led to the Apollo 11 landing and the end of the Cold War eventually dissolved into a steady state. The aerospace supply chain shifted from urgent to long-term posture. Winners and losers solidified their spots in the hierarchy, processes were refined, and incentives across the space, defense, and civil aviation sectors reinforced incrementalism.

Along the way, industry consolidation sped up, rolling up specialized shops into in a small number of large aerospace companies that manage their finances by quarters to appease public investors. From the 1970s until now, the U.S. enjoyed mostly unchecked global supremacy in technological, economic, and military strength. So, the aerospace supply chain oriented its expectations – and, eventually, its entire culture – around incrementalism. “Good enough” was the goal, and everyone wanted to crush costs at all costs. A zero-risk mentality took hold.

The innovation imperative

At some point, every zero-risk mentality gives way to zero-boundaries thinking. “Necessity is the mother of invention” is just another way of saying “urgency drives innovation.” After decades of incrementalism, aerospace is finally experiencing urgency on the level of the first Space Race, across all sectors:

- Defense aerospace is feeling the pressure of a military technology development process that has lagged well behind other nation-states. China, for example, reportedly sent a hypersonic missile all the way around the globe, with broad implications on national security and, importantly, the speed and scale of U.S. military innovation timelines. We all know about Russian saber-rattling over nukes in connection with the Ukraine invasion. These are just the most recent and visible wake-up calls. The widespread realization of this American innovation lag has led to calls to ramp up digital engineering capabilities and a record $130 billion in military research and development in the White House’s FY23 budget proposal. To paraphrase the Uruk-hai, "Looks like innovation is back on our menu, boys!"

- Space has seen NASA cede the launch platform to corporations like SpaceX, Blue Origin, Rocket Lab, Astra, and Firefly, among others. These companies are literally racing to secure their spots atop the emerging space value chain to access huge potential markets. Space mining represents hundreds of billions, if not trillions, in wealth and promises to break up raw material monopolies in resource-rich countries like China and Russia. There are also immense technical, environmental, and productivity benefits to manufacturing in space, to say nothing of burgeoning markets like logistics and earth observation that make use of low-earth orbit satellites. Investors pumped at least $14 billion into space companies in 2021, a record.

- Commercial aviation is still dominated by Airbus and Boeing, but innovation pressure is reshaping the civil sector as well. Investors are dumping obscene amounts of growth capital into startup companies trying to perfect commercial supersonic travel, spin up electric fleets for regional flights, and get electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) vehicles – or “flying taxis,” if you prefer – off the ground in a city near you. Our single-mode way of flying could soon be disrupted, with today’s upstarts eventually owning a meaningful slice of local, regional, domestic, and international air travel.

So, uh, yeah. There’s a lot of innovation pressure in aerospace. In fact, our CEO, Brian McCann, co-wrote an article for Utah Business magazine with Greg Manuel, head of Northrop Grumman’s Strategic Deterrent Systems division, in which he coined the term “innovation imperative” to describe this massive ball of urgent energy.

Supply chain pressures

Innovation might start at the top of the value chain, but it always flows down. Think about the consumer internet. Way back in the early 2000s, you could just find a business’s phone number on their website to call and place a traditional phone order. Then, you could fill out a form and place an order online. Later, you could pay for that order with a credit card tied to your account. Now, you can do all that and get whatever you want delivered in a day or two without ever interacting with an actual human.

For the consumer internet, opportunities at the top of the internet food chain created innovation pressures all the way down. For example, legacy credit card processors struggled to adapt their business models to a world run by software engineers, making room for digital era mega-successes like Square and Stripe to dominate online payments. It was a classic disruption scenario, and there are dozens more examples in the internet's history to date.

The same thing is happening in aerospace right now. Innovations at the platform level *require* innovation in the supply chain, as well. There are technical problems, like thermal regulation (ahem!), that can’t be solved by legacy solutions that have been around for 70 years. It’s tough for legacy companies to innovate fast enough to solve these constraining problems because their cultures and incentives don’t align with responding to disruptive pressures. As the father of the “disruption” concept, Clay Christensen, said:

“The reason why it is so difficult for existing firms to capitalize on disruptive innovations is that their processes and their business models that make them good at the existing business actually make them bad at competing for the disruption.”

As we like to say at Intergalactic, you can’t build tomorrow’s breakthroughs with yesterday’s technologies. Innovation is no longer optional, especially in the aerospace supply chain.

Follow the money

One very good barometer that an industry is about to be disrupted is when venture capital starts flowing into it. Institutional investors are very good at recognizing markets that are about to pop or pivot. It’s telling, then, that a few of venture capital’s most iconic firms recently poured a ton of money into Hadrian, a startup that is trying to reimagine the model for manufacturing machined parts for the aerospace industry.

For Hadrian, the factory is the product. The company has innovated a scalable factory model that uses automation to create, the company claims, 10x efficiencies in producing precision aerospace components. Hadrian’s lead investors, Andreessen Horowitz and Lux Capital, recently revealed some key insights about how they’re viewing the aerospace market in blog posts about their investment in Hadrian:

- From a16z’s Katherine Boyle: “The defense industrial base is served by a network of thousands of small machine shops across the country, often run by very talented machinists who have spent a lifetime honing their craft. The average age of a lead machinist in America is now hovering around the mid 50s, and like other skilled trades, the coming retirement of the Boomers is leading to a dangerous labor shortage in an important industry. Beyond even the lack of skilled labor to make critical parts, there’s the thorny question of security and supply chain transparency, which our commercial aerospace industry is desperate to see fixed as it grows in scale and importance.”

- From Lux’s Danny Crichton: “...(O)ur view that space has limitless potential for economic growth has only expanded and intensified over the past years. The rapidly improving cost calculus for space flights is empowering a whole new generation of uses for launch vehicles, from manufacturing and pharmaceutical research to installing satellite constellations in low-earth orbit. Meanwhile, increasing geopolitical competition between the United States, China, Russia, India and others has made space an important environment for national supremacy.

The aerospace industry is feeling innovation urgency not seen since the Space Race, with implications across all sectors. As a result, the entire aerospace supply chain is being remade – in slow motion for now, but accelerating soon. Tomorrow’s winners and losers are being made today. Innovate or die.

- Brad Plothow, Intergalactic Chief Growth Officer