UH-60 Black Hawk: The Army’s workhorse utility helicopter

Blog

The Bell UH-1 Iroquois, the iconic “Huey” of the Vietnam era, was ubiquitous during that conflict and changed the nature of mobilized infantry. Anyone who has lain on a sweltering motel-room bed, looking up at the spinning ceiling fan, listening to the Doors and pretending to be Captain Willard is familiar with the “chop-chop” soundtrack of the Huey’s twin-bladed propeller. However, even before the end of the Vietnam war, the Army recognized the Huey’s limitations and started looking for a replacement utility helicopter platform with greater performance, range, carrying capacity, and above all, survivability. The result was the UH-60 Black Hawk, named after the native Sauk warrior and leader. (The US military has an arguably ironic tradition of naming its helicopters after prominent Native American leaders or tribes—Iroquois, Chinook, Apache, Lakota, Sioux, etc. It’s intended as a compliment, we promise.)

First entering service in 1979, the Sikorsky UH/HH-60 Black Hawk is the Army’s go-to utility tactical transport helicopter, and the platform is also in use by the Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard, as well as US Customs and Border Protection. It provides the Army with air assault, general utility, aerial medical evacuation, command and control, and special operations support capabilities. The versatile helicopter has enhanced the Army’s overall mobility due to dramatic improvement in troop and cargo lift capacity compared to legacy airframes, along with significantly improved resistance to enemy fire and ground impacts. The UH-60 platform has proven so effective, adaptable, and reliable that it’s been in continual service for over 40 years, with at least 20 more years planned before retirement. Let’s go over what makes this multipurpose “flying tank” so good.

The search for a helicopter with greater survivability

As we mentioned above, the UH-1 “Huey” transformed the way mobile infantry is deployed and supported. The ability to insert fully armed combat troops into specific areas with pinpoint accuracy, and without the dangers and expense of imprecise parachute drops, was a complete game-changer. The Huey was also instrumental in the medevac transport role, which increased the efficiency of getting wounded troops to hospitals.

However, though the UH-1 Iroquois was a crucial leap forward in “Air Cavalry” mobile-infantry warfare, the military learned some very painful lessons through the Huey’s combat history in Vietnam. Around 7,000 UH-1s were used and flown during the conflict, but at least 3,300 of them were shot down, killing 2,100 pilots and crew members, not including any troops aboard. That means that nearly half of the Huey fleet was lost in combat… not a stellar survivability record by anyone’s estimation.

As a result of these losses, in the late 1960s the Army began planning a program to develop a replacement helicopter for the UH-1 Iroquois. The program was called the Utility Tactical Transport Aircraft System (UTTAS), and based on the lessons learned in Vietnam, the Army’s UTTAS requirements included significant improvements in reliability, maintenance requirements, “hot and high” condition performance, modularity, robustness of main and tail rotor systems, and crucially, an armored crew cabin, crashworthy seats and landing gear, and a “ballistically tolerant” fuel system. In other words, survivability.

Along with the UTTAS, the Army also initiated the development of a new, common turbine engine for its helicopters that would become the General Electric T700. This would greatly streamline the supply chain and maintenance requirements across all military helicopters, since they would all utilize the same turbine powerplant. The Army released its UTTAS request for proposals (RFP) in January 1972, and Sikorsky was awarded the budget to build four YUH-60A prototypes for evaluation against the competing Boeing-Vertol design, the YUH-61A. The first YUH-60A flew on 17 October 1974. After flight testing and evaluations, the Army selected the UH-60 for initial low-rate production in December 1976 and awarded Sikorsky a limited contract as well as funding for the Maturity Phase and Producibility Engineering Phase.

The first UH-60A, built during the first year of low rate initial production, was delivered to the Army in 1978 and entered service with the 101st Combat Aviation brigade of the 101st Airborne Division in June 1979. The platform first saw combat during the invasion of Grenada in 1983, and has served faithfully in every US conflict since.

Interestingly, the Sikorsky contract focused on building an “underweight” aircraft, to allow for additions of potential equipment and weapons deemed necessary during the evaluation phase. Sikorsky was able to cut the production weight of its UH-60 by an amazing 1,000 pounds compared to the prototypes.

UH-60 Black Hawk specifications, carrying capacity, speed, and range

The UH-60 uses self-sealing, crash-capable fuel tanks, dual-stage impact-absorbing main landing gear, impact-absorbing chairs for crew and passengers, tail rotors and improved 4-blade main rotors constructed of ballistically resilient material, armor plating around the cockpit, and two powerful General Electric T700 (or upgraded GE-701) turboshaft engines rated at 1,560 shaft horsepower each, capable of lifting the “flying tank” fuselage of the Black Hawk plus an additional 9,000 lbs as sling cargo, and cruising away at over 100mph with that load. It has a maximum speed of 183 mph, cruises at 175 mph (without any sling cargo), has a combat range of 370 miles, and a maximum ferry range of 1,380 miles with additional external and internal fuel tanks installed. The Black Hawk has room for up to 4 crew members plus 11 to 14 fully armed troops (depending on number of crew), or up to 20 lightly equipped passengers.

Internal fuel totals 360 gallons. If properly equipped, the Black Hawk can carry two additional 230-gallon external tanks, and up to two additional auxiliary 185-gallon tanks internally in the cargo compartment. The Black Hawk has redundant systems for all vital controls, and is capable of flying on one engine.

By all metrics the UH-60 was a huge success, is currently in use by 34 countries worldwide, and rolling improvements over the decades have kept the airframe relevant and effective as technological and strategic requirements have changed.

What are the different versions of the UH-60 helicopter?

There have been multiple versions of the UH-60 Black Hawk (versions A through L) used by the Army, including the UH-60M and the UH-60V. The current UH-60M includes the improved GE-701D engine which provides greater cruising speed, rate of climb, and internal load capacity compared to the UH-60A and UH-60L versions. The forthcoming UH-60V is intended to update the existing UH-60L’s analog architecture to a digital infrastructure, enabling the upgraded aircraft to have a similar Pilot-Vehicle Interface and commonality of training with the UH-60M.

The medical evacuation (MEDEVAC) version of the UH-60M, the HH-60M, includes an integrated medevac mission equipment package kit, providing day, night, and adverse weather emergency evacuation of casualties, including room for up to 6 litters at a time.

The SH-60 Sea Hawk (or Seahawk) is the US Navy’s version of the UH-60, and is the primarily medium-utility helicopter in the Navy’s fleet. The Seahawk is used for anti-submarine warfare, search and rescue, drug interdiction, anti-ship warfare, cargo lift, and special operations. The Navy’s SH-60B Seahawk variant is based aboard cruisers, destroyers, and frigates, and serves in an anti-submarine role. The SH-60B carries a complex system of sensors including a towed Magnetic Anomaly Detector (MAD) and air-launched sonobuoys, as well as torpedoes. Other sensors include the APS-124 search radar, which extends the range of the host ship’s radar capabilities. The Navy’s variant also includes the ALQ-142 ESM (electronic support measures) system and optional nose-mounted Forward Looking Infrared (FLIR) turret. The Navy’s SH-60F is the carrier-based variant.

Some versions of the helicopter, such as the Air Force’s MH-60G Pave Hawk and the Coast Guard’s HH-60J Jayhawk, are equipped with a rescue hoist with a 250 foot (75 meter) cable with a 600 pound (270 kg) lift capability, and a retractable in-flight refueling probe. The UH-60 has 2 pintles for mounting machine guns and can also carry and launch rockets and Hellfire missiles, though the Black Hawk is not designed or intended as a primary strike aircraft.

There are multiple other sub-variants and export versions of the platform with specialized configurations and capabilities, and there’s even a VH-60N Marine Corps variant that serves as Marine One when transporting the president of the USA.

How much does a Black Hawk helicopter cost and what’s the program budget?

The most accurate information we could find for the total budget and cost per unit for the Black Hawk helicopter comes from the Department of the Army’s Selected Acquisition Report made public in April 2022, which outlines the procurement, development, and acquisition costs of the UH-60M model with its upgraded engines. Since the program’s approval in 2001, the total acquisition cost for the UH-60M program specifically is $22.6 billion, with a Program Acquisition Unit Cost (PAUC) of $16.3 million per helicopter in “base year” dollars, or $20.37 million in “then year” dollars based on the 2023 budget.

Other sources cite the cost of the UH-60L Black Hawk at $5.9 million while the unit cost of the Air Force’s HH-60G Pave Hawk is $10.2 million. However, it’s unclear whether those quotes have been adjusted to current-year dollars. Unclassified Army budgetary request documents (if we’re reading them correctly—remember, we’re just rocket scientists, not bureaucratic government accountants) show the cost of converting the UH-60A through UH-60L to the upgraded, digital-friendly UH-60V to be around $4.8 million per helicopter in 2023 dollars, with the total cost per unit of the UH-60V at around $21.1 million.

How many UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters are in service?

More than 4,000 Sikorsky S-70 (the international designation) or H-60 helicopters of all variants are in service today worldwide. The US Army is by far the largest operator with 2,135 H-60 type aircraft flying. Budget requests show the Army purchasing between 25 and 36 new UH-60s per year over the past 4 years.

Crashes and fatalities involving the UH-60 Black Hawk platform

As recently as March 2023, two Black Hawks were involved in a crash during a nighttime training mission in Kentucky, killing all 9 servicemembers aboard. This is unfortunately not an uncommon event, as the Army’s data shows there have been 60 deaths in Black Hawk-related training incidents over the past decade alone. However, these concerns surfaced essentially from the beginning of the adoption of this helicopter platform, as Military.com reports: “In 1985, the Army ordered all of its Black Hawks grounded after six crashes and 15 deaths in a four-month period that followed 22 deaths related to Black Hawk crashes from 1981 to 1984.”

While any fatal accident involving service members is tragic, it’s important to realize that the relatively large numbers of fatalities involving UH-60 helicopters coincide with the enormous numbers of flight hours and widespread use of the platform over the decades. If we look at comparative fatality figures per flight hour, the Black Hawk family is actually among the safest military helicopters ever flown.

The Army’s figures show that Black Hawks account for 63% of the Army’s total helicopter fleet, but make up the fewest incidents when adjusted for hours flown. The data shared with Military.com shows one serious mishap, usually involving a fatality, for every 100,000 UH-60 hours flown across the Army, Army Reserve and National Guard between 2012 and 2022. Black Hawks flew a cumulative 326,162 hours in 2022.

By comparison, the AH-64 Apache accounts for 21% of the military’s helicopter inventory but has roughly double the fatal incidents as the Black Hawk, with 1.93 serious incidents per 100,000 flight hours. Furthermore, the Apache carries only a two-person crew, whereas the UH-60 can hold up to 4 crew members and a dozen or more troops. This means that catastrophic accidents involving the Apache typically result in fewer deaths per incident. Considering this, the 1.93 serious accidents per 100K flight hours record of the Apache shows that the Black Hawk is almost twice as safe, and the numbers look even better when you consider that the maximum casualties per incident is potentially much higher in the Black Hawk.

Furthermore, the CH-47 Chinook heavy transport helicopter can fit more than 30 passengers and it accounts for more fatal incidents than Black Hawks, even though Chinooks make up just only 15% of the Army’s helicopter fleet. The Chinook’s average major incident record of 1.59 per 100,000 flight hours is nearly 60% worse than the Black Hawk. (All of this data strictly covers training incidents, not combat losses.)

A report published in Aircraft Survivability in Summer 2010 listed a total of 375 US helicopters lost in Iraq and Afghanistan up to 2009. Of these, 70 were downed by hostile fire, while the other 305 losses have been classified as non-hostile or non-combat events. But this figure includes all helicopter types, and an analysis of the data shows that only a fraction of these losses involved the Black Hawk.

As of March 2023, Aviation Safety Network lists 390 total crash incidents involving Black Hawk helicopters (including variants). ASN data lists 970 total deaths in Black Hawk helicopter crashes. The vast majority of these are during training exercises.

Even if we considered all of these incidents as combat losses, the Black Hawk would still be far safer and much improved in survivability compared to the UH-1 it replaced, and is among the safest military helicopters ever fielded. The UH-60 family looks to have a long and useful life remaining. Maybe we can even rig up some surfboard mounts for Colonel Kilgore.

Thermal management on the UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter

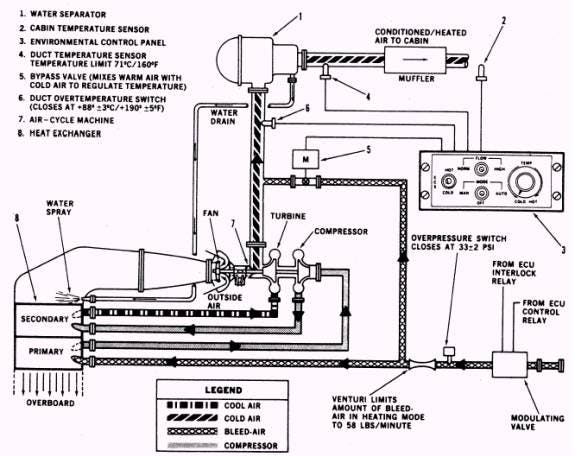

We’re in the business of aerospace thermal management, so we’re pretty geeked to learn more about the thermal system on this iconic helicopter. At least in the Seahawk variants, air is bled off from the engines (400 F and 40 psi) and fed through a modulating valve to the primary heat exchangers. The cooled bleed air (200 F) is further compressed (300 psi) and routed through the secondary heat exchanger. Then the highly compressed, cooler air (150-200 F) is expanded in a turbine back to ambient pressure and work is extracted to power the compressor and fan. When the air is expanded, the temperature drops to just above freezing. The warm bleed air, direct from the engines, is mixed with the cold air to maintain the desired air temperature. A water separator extracts free water from the cool air and that water is sprayed over the heat exchangers to increase their efficiency. The fan draws in free stream air from outside the aircraft and blows it across the heat exchangers. The conditioned air is primarily used for keeping the avionics cool.

–By Jeff Davis, Intergalactic Scribe

Sources:

https://www.military.com/equipment/uh-60a-l-black-hawk

https://asc.army.mil/web/portfolio-item/black-hawk-uhhh-60/

https://www.military.com/equipment/sh-60-sea-hawk

https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/products/sikorsky-black-hawk-helicopter.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sikorsky_UH-60_Black_Hawk

https://www.wisnerbaum.com/aviation-accident/helicopter-crashes/black-hawk-helicopter-crashes/